Introduction

While discourse about value-based care has become especially pervasive these days, we’ve noticed that sometimes the nuances may be glossed over, especially in the emerging healthtech space. Yes, VBC incentivizes quality over volume, and yes, access to data (our bread and butter!) is crucial for success. However – which data levers specifically might have the highest impact on care outcomes? On business results? How does this differ across the different types of value-based care? Today, providers have access to many different types of health data (first-party data generated in their EMR, third-party data from national exchanges, claims data) – where can each of these data types be most useful?

Great resources are available about each of these themes independently. However, given the early stage of what we focus on at Zus (namely, third-party clinical data interoperability), we thought it would be helpful to examine the different types of value-based care and how real-time clinical data might be able to move the needle on outcomes and cost.

As the first post in this multi-part series, we dive into the background of value-based care and the most common models today.

Background

Over the last decade or so, the healthcare world has seen a shift – away from more traditional fee-for-service (FFS) payment models towards value-based care (VBC), a reimbursement model that rewards physicians for longer-term health outcomes. VBC has received increasing support, especially from the U.S. government, as an alternative to the FFS model that has continued to underperform both in terms of ridiculously high costs and underwhelming health outcomes. The hope for VBC is not only to decrease unnecessary spending, but also to provide better and more equitable care for everyone.

While traditionally practitioners are compensated for each service provided to patients, value-based care models instead provide financial incentives for providers that achieve certain quality metrics (related to chronic disease management, cancer screenings, etc.). One of the largest forces behind this movement has been the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which has been laser-focused on finding new ways to improve care and decrease spending in healthcare: by 2030, CMS has set the ambitious goal to transition 100% of Medicare patients to accountable care relationships. In their effort to do so, CMS has partnered with payers and healthcare providers across a range of value-based care models.

Before going into some of the most common models, we’ll look at the Affordable Care Act to better contextualize VBC today.

Prefacing VBC: The Affordable Care Act

While value-based care models didn’t begin with the adoption of the Affordable Care Act signed in 2010, the historical context and groundwork that the ACA laid was integral for the widespread adoption of VBC. Provisions in the ACA allowed for CMS to adopt and experiment with alternative payment models, primarily through the creation of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI); these experiments have yielded mixed results over the course of CMMI’s first 10 years.

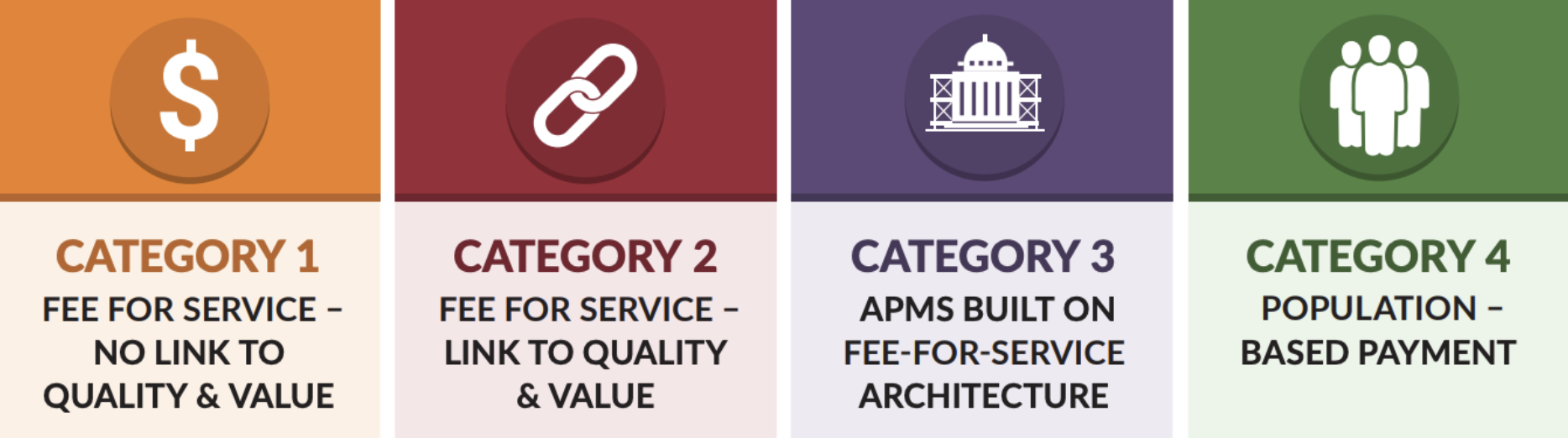

With this foundation of experimentation, value-based care is typically best defined by what it is not: “open-ended fee-for-service payments, or straight pay for volume,” as this Health Affairs brief aptly puts it. To help structure discussions around value-based care, the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network created a framework for categorizing these models that is used broadly across the industry, with categories 3 and 4 representing different flavors of what we consider to be value-based care.

According to a 2020 analysis conducted by the LAN, the share of U.S. healthcare payments flowing through categories 3 or 4 meaningfully increased over the past five years, growing from an estimated 23% in 2015 to 41% in 2020. However, adoption rates vary across payer categories: Medicare Advantage had 58% of its payments associated with an alternative payment model, traditional Medicare, primarily through Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) saw 42.8% of its payments in category 3 or 4, Medicaid had 45.4%, and commercial payers had 35.5%. Given the different payment models, each of these payer groups has slightly different incentives and goals with their value-based care programs.

Medicare Advantage

CMS has allotted many resources towards enrollees in Medicare Advantage (MA) programs, which serve as a capitated alternative to regular Medicare plans. Under this structure, the government pays private insurance companies a risk-adjusted, per-member-per-month rate to cover the healthcare costs of Medicare beneficiaries that opt into the program (instead of using Original Medicare). MA has served as a key backbone of the efforts to move towards value-based care: since payers are compensated through a PMPM model, it encourages minimizing healthcare spending, which has made it easier to focus on moving away from encounter-based care. Medicare Advantage is quickly becoming one of the most popular forms of Medicare: in 2022, there were more than 28 million MA enrollees, accounting for 48% of the eligible Medicare population, and total spending reached $427 billion, representing 55% of total Medicare spending. For payers and their provider partners, MA is often extremely lucrative if they are able to effectively manage the care of the seniors attributed to them.

Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)

Considered part of Original Medicare, an Accountable Care Organization is a group of hospitals, doctors, or practices that join together to provide coordinated high-quality care for their patients and, much like other forms of value-based care, have the potential to be compensated via a shared savings agreement. Typically, ACOs are financially rewarded when they succeed in reducing spending growth in Medicare Parts A and B relative to their benchmark, while achieving quality performance standards across their population. ACOs have become a relatively popular option for practices transitioning into value-based care, with an estimated 13 million Medicare enrollees (about 12%) receiving care through an ACO in 2022. The two largest ACO types are the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), which accounted for 10.9 million beneficiaries in 2022, and ACO REACH, a newer model focusing on health equity and access that accounted for about 2.1 million beneficiaries.

There are multiple types of ACOs, but the core of the model remains generally consistent; interested providers typically choose the program that best aligns with their own practice profile and patient population. Within certain ACO types, there have been promising results: in 2021, the Medicare Shared Savings Program saved Medicare $1.66 billion compared to spending targets, while still delivering high-quality care.

Medicaid

The cornerstone of value-based care in Medicaid is the managed care organization (MCO), which typically provides comprehensive risk-based care to beneficiaries and receives a set per member per month payment for these services. As in Medicare, the goal of value-based care in Medicaid is to improve health outcomes for its 90M+ enrollees, improve patient experiences, and control healthcare costs. In 2020, 72% of Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in comprehensive MCOs, although the specific benefits and payment vary state-by-state. It’s worth noting that just five companies – Centene, Anthem, UnitedHealth Group, Molina, and Aetna/CVS – control half of the Medicaid MCO market, and typically see Medicaid as a major source of revenue.

In tandem with MCOs, state Medicaid programs also use payment reform models like patient-centered medical homes, ACA Health Homes, accountable care organizations, and episodes of care. State-specific case studies have demonstrated savings generated through these efforts: for instance, Colorado’s Regional Care Collaborative Organizations report saving $77 million in net savings for Colorado Medicaid, along with yielding lower rates of emergency department visits and hospital readmissions for adult patients. However, these results remain fairly patchworked across states, and CMS is working with states via new regulation to require them to adopt a CMS-developed quality rating system or an alternative system approved by CMS.

Commercial

As is common in the healthcare space, commercial trends tend to follow efforts that are first spearheaded by the government. For VBC, this means that commercial plans have begun to work with healthcare organizations to adopt plans whose reimbursement is focused on lowering healthcare spending and improving health outcomes. With the transition occurring via programs like Medicare Advantage and ACOs, commercial plans are often structured in similar ways and use CMS’ predetermined quality metrics like HEDIS to measure outcomes and define success. In some cases, the commercial world of value-based care has moved beyond the templates established by the government and experimented with additional alternative payment models. For instance, direct primary care and other capitation-based models have been on the rise as physicians seek to improve their patients’ outcomes and grow increasingly frustrated with the FFS model.

Concluding Thoughts

The healthcare world’s shift towards value-based care is here, but as with the rest of healthcare, lack of data and inefficient systems have made it unnecessarily difficult for physicians to make that transition. And, like the rest of healthcare, having access to the right tools and data has the potential to make value-based care a lot more effective for patients, physicians, and payers. We at Zus are excited that our mission to create a world of true healthcare data interoperability will be able to support a new care model with patient care at the center.

Featured photo by Çağlar Oskay on Unsplash